Arabic Calligraphy: Sacred Lines and Cultural Legacy in the Arab-Islamic World

A deep exploration of Arabic calligraphy as both a visual art form and a vessel of cultural memory, power, and modern expression.

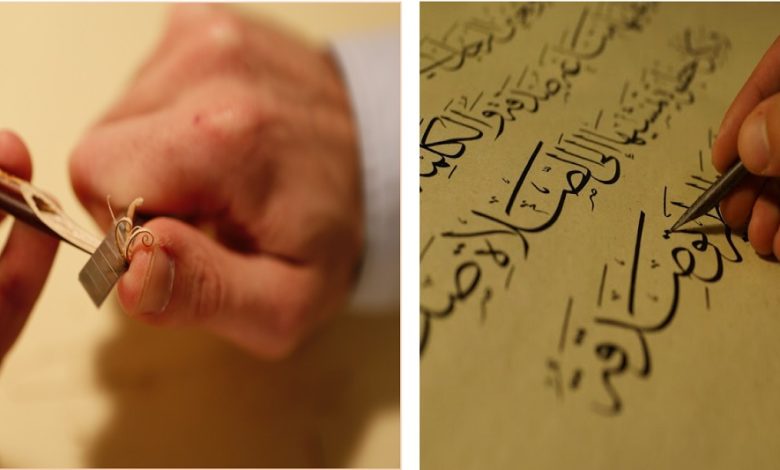

Arabic calligraphy is more than an artistic discipline—it is a civilizational expression rooted in spirituality, governance, and identity. From Qur’anic manuscripts and palace walls to revolutionary graffiti and digital branding, the calligraphic script has served as both scripture and symbol, aesthetic and authority. What makes Arabic calligraphy unique is that it has evolved not just as a craft, but as a philosophy of language made visible.

1. Script as Revelation: The Qur’anic Catalyst

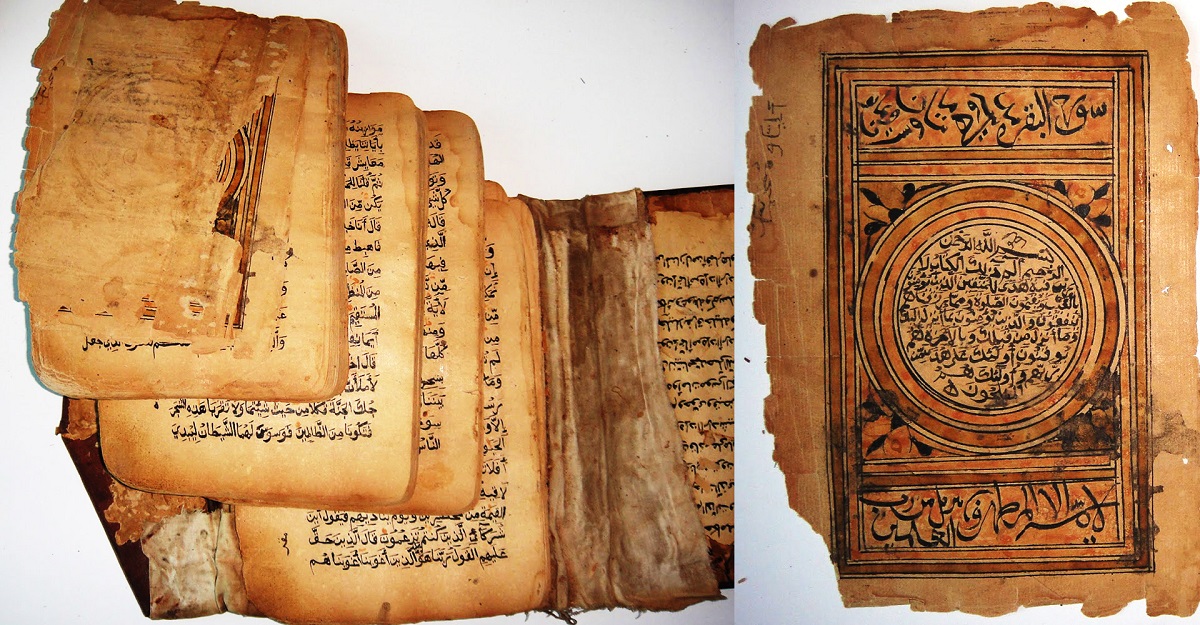

The origins of Arabic calligraphy cannot be understood without recognizing its relationship with the Qur’an. Arabic, as the language of divine revelation in Islam, was elevated from a tribal dialect into a sacred code. Early Muslims developed calligraphy to preserve the Qur’an accurately and honor its form.

This reverence for the written word made Arabic calligraphy a spiritual discipline. The early Kufic script—bold, angular, and geometric—dominated Qur’anic inscriptions in the Umayyad and Abbasid periods. Calligraphy was not decorative—it was devotional, a sacred geometry that mirrored divine order.

“The first thing God created was the pen,” states a prophetic hadith—a sign of the cosmic significance of writing in Islam.

2. Evolution of Styles: From Kufic to Diwani

Arabic calligraphy diversified into multiple styles across time and regions. Each script reflects the philosophical, political, and aesthetic needs of its era:

-

Kufic: Used in early Qur’ans, coins, and monuments. Known for its architectural precision.

-

Naskh: A rounded, legible script developed by Ibn Muqlah in the 10th century; widely used in books and daily writing.

-

Thuluth: Ornate and complex, seen in mosque inscriptions, banners, and titles.

-

Diwani: An Ottoman invention, curved and flowing, often used in royal decrees.

-

Maghribi: A North African script with wide, sweeping curves, used in Andalusian texts.

Each of these styles is governed by mathematical proportion, yet allows for individual expression. The master calligrapher balances discipline and creativity, much like a Sufi balancing self-restraint with divine love.

3. Calligraphy as Political Power and Identity

Arabic calligraphy has been used by rulers and empires as a tool of political legitimacy and authority. The Abbasids, Ottomans, and Fatimids commissioned elaborate inscriptions in mosques, palaces, and official documents. To control the word was to control the message.

In colonial and postcolonial periods, Arabic calligraphy became a symbol of resistance. Anti-colonial movements in Algeria, Palestine, and Iraq used Arabic script in posters and revolutionary literature. Today, street artists in Cairo, Beirut, and Gaza blend calligraphy with modern graffiti—a movement known as “calligraffiti”—to reclaim public space and assert identity in the face of repression or globalization.

4. Calligraphy in Modern Art, Tech, and Design

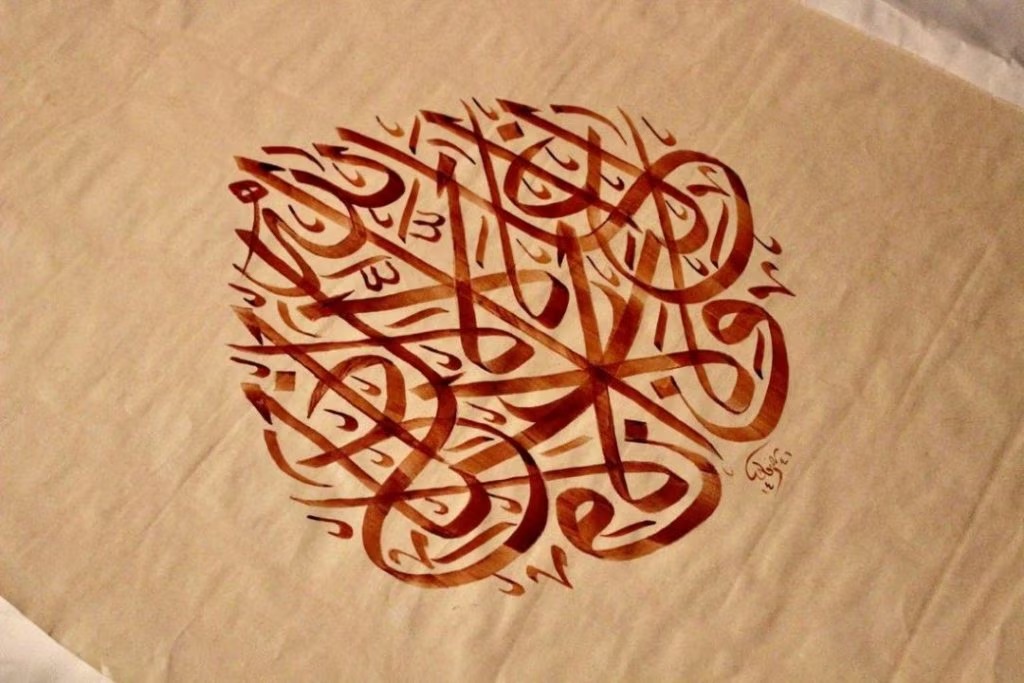

Contemporary artists have reimagined Arabic calligraphy in digital, abstract, and mixed-media forms. Artists like Hassan Massoudy, El Seed, and Nja Mahdaoui merge tradition with innovation. Their work appears in museums, fashion, architecture, and social media—reaching a global audience.

Arabic calligraphy is now digitized and democratized: available in thousands of fonts, used in apps and branding, adapted for tattoos and streetwear. While this opens up access, critics warn of aesthetic dilution—where calligraphy becomes stylized decoration divorced from its sacred or cultural roots.

Yet others argue that this evolution is a continuation, not a rupture—a proof that Arabic calligraphy is a living, breathing language of form.

5. Philosophical and Mystical Dimensions

Arabic calligraphy has long had mystical undertones. In Sufism, the shape of each letter is seen as symbolic. For example:

-

The alif (ا) represents divine unity and transcendence.

-

The ba (ب)—with its single dot beneath—symbolizes hidden knowledge (baṭin).

-

The circular scripts like Thuluth represent the infinity of the divine, echoing the whirling of the dervish.

Calligraphy in this context is not just art—it is meditation, contemplation, and dhikr (remembrance of God). Many calligraphers describe the act of writing as an inner purification.

Conclusion: The Enduring Soul of the Script

Arabic calligraphy is not static. It has traveled across time, empires, and oceans—adapting while preserving its soul. For Arabs in the diaspora, it remains a visible link to language, heritage, and homeland. In a world flooded with images and algorithms, Arabic calligraphy endures as a slow, intentional, meaningful form of beauty—a reminder that letters can still carry spirit.