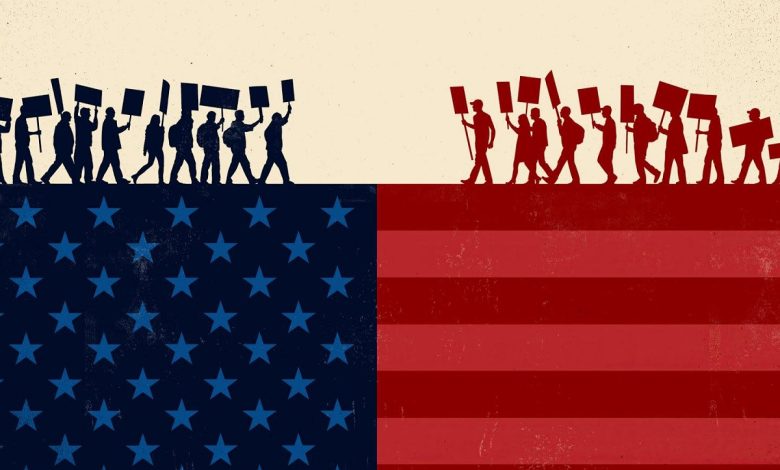

America’s Deepening Divide: How Binary Thinking Shapes a Polarized Nation

From the assassination of Charlie Kirk to the growing distrust among Americans, a culture of “us versus them” continues to define political and social life.

The United States is experiencing one of the most intense periods of polarization in its modern history — a divide deepened by politics, ideology, and identity. This growing fracture became especially visible following the assassination of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk on September 10 during a public event at the University of Utah.

In his New York Times essay “Why Do Americans Disagree About Everything?”, writer Mark Edmundson explores the roots of this division, noting that Americans increasingly view national issues through the lens of absolute opposition — right versus wrong, friend versus foe. A Times/Siena poll he cited revealed that a growing number of Americans now believe the nation is so polarized that solving problems cooperatively has become nearly impossible.

Edmundson argues that this divide reflects a dominant cultural mindset — binary thinking, the habit of reducing everything to two extremes. This dualistic approach, he says, can be seen everywhere: in politics, dominated by two major parties that constantly clash; in media, which amplifies outrage and contrast; and even in sports, where fans are conditioned to think in terms of winners and losers.

Drawing from psychology, Edmundson — author of The Age of Guilt: The Super-Ego in the Online World — describes binary thought as a form of surrender to what Sigmund Freud called the “narcissism of small differences,” a psychological mechanism that sustains hostility even among similar groups.

Still, he acknowledges that binary thinking isn’t always destructive. It can sometimes help clarify complex choices and guide decision-making. But over time, it fosters a culture of judgment and alienation. The late French philosopher Jacques Derrida, he recalls, devoted much of his work to dismantling binary thought, warning that constant opposition breeds antagonism and even violence. Derrida instead promoted intellectual freedom — thinking that embraces connection and complexity rather than opposition.

In closing, Edmundson calls for a new mindset grounded in curiosity and empathy rather than division. “We all share the same spirit,” he writes. “This outlook does not provoke opposition or conflict; it accepts what it encounters without bias or incitement.”